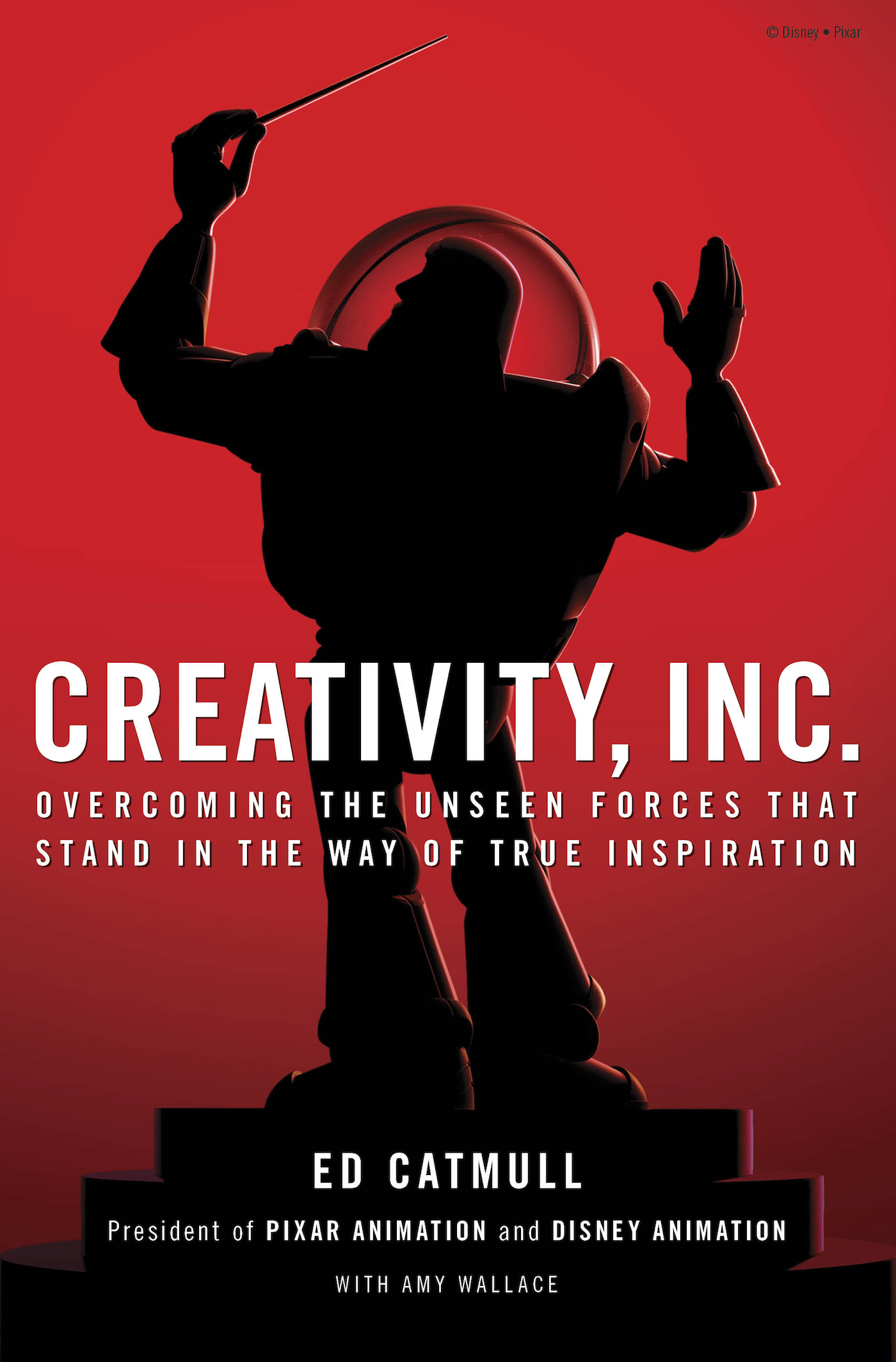

Creativity, Inc.

I’ve read about this book on a couple of websites, so when I saw it at a local store specialized in english books, I grabbed a copy. My trip to Iceland was coming up too, so it would make for a good occupation if I would get bored.

For me, the author Ed Catmull will always be the guy that co-invented the Catmull-Rom spline, something I learned in 15-462 Computer Graphics 1 with Jessica Hodgins at CMU. Turns out, that’s probably one of the smaller achievements of his life, to say the least. After all, he co-founded Pixar.

I’m probably not at all the target audience of this book, but I enjoyed it very much. I loved having insights on the inner workings of my all-time favorite company, Pixar. I also learned more about how Steve Jobs more or less saved Pixar early in its history. All very interesting stuff. However after John Siracusa on ATP #76 brought up Catmull’s implication in wage fixing, I took everything I read with a grain of salt. I guess nobody’s perfect.

I don’t know if copyright laws allow me to quote the book, but considering the tiny audience of this site, I don’t think I take a big risk. So here are a bunch of my favorite parts of Creativity, Inc.

What’s more important: people or ideas?

The takeaway here is worth repeating: Getting the team right is the necessary precursor to getting the ideas right. It is easy to say you want talented people, and you do, but the way those people interact with one another is the real key. Even the smartest people can form an ineffective team if they are mismatched. That means it is better to focus on how a team is performing, not on the talents of the individuals within it. A good team is made up of people who complement each other. There is an important principle here that may seem obvious, yet —in my experience— is not obvious at all. Getting the right people and the right chemistry is more important than getting the right idea.

No matter whether I was talking to retired business executives or students, to high school principals or artists, when I asked for a show of hands, the audiences would be split 50-50. (Statisticians will tell you that when you get a perfect split like this, it doesn’t mean that half know the right answer —it means that they are all guessing, picking at random, as if flipping a coin.)

People think so little about this that, in all these years, only one person in an audience has ever pointed out the false dichotomy. To me, the answer should be obvious: Ideas come from people. Therefore, people are more important than ideas.

I had the discussion with several people about is there such a thing as talent? It seems that Ed Catmull has the same opinion as I do:

People have come up to me many times […] and said, ‘Gee, I wish I could be creative like you. That would be something, to be able to draw.’ But I believe that everyone begins with the ability to draw. Kids are instinctively there. But a lot of them unlearn it. Or people tell them they can’t or it’s impractical. So yes, kids have to grow up, but maybe there’s a way to suggest that they could be better off if they held onto some of their childish ideas.

Later in the book, he comes back to this concept. And I can relate so much with what he says. I’m scared of trying to draw again :(

We begin life, as children, being open to the ideas of others because we need to be open to learn. Most of what children encounter, after all, are things they’ve never seen before. The child has no choice but to embrace the new. If this openness is so wonderful, however, why do we lose it as we grow up? Where, along the way, do we turn from the wide-eyed child into the adult who fears surprises and has all the answers and seeks to control all outcomes?

It puts me in mind of a night, many years ago, when I found myself at an art exhibit at my daughter’s elementary school in Marin. As I walked up and down the hallways, looking at the paintings and sketches made by kids in grades K through 5, I noticed that the first- and second-graders’ drawings looked better and fresher than those of the fifth-graders. Somewhere along the line, the fifth-graders had realized that their drawings did not look realistic, and they had become self-conscious and tentative. The result? Their drawings became more stilted and staid, less inventive, because they probably thought that others would recognize this “fault.” The fear of judgment was hindering creativity.

If fear hinders us even in grade school, no wonder it takes such discipline —some people even call it a practice— to turn off that inner critic in adulthood and return to a place of openness.

Here’s something I think I still do wrong at work. Maybe because I’m still not confident enough (and probably never will be).

There’s a quick way to determine if your company has embraced the negative definition of failure. Ask yourself what happens when an error is discovered. Do people shut down and turn inward, instead of coming together to untangle the causes of problems that might be avoided going forward? Is the question being asked: Whose fault was this? If so, your culture is one that vilifies failure. Failure is difficult enough without it being compounded by the search for a scapegoat.

About how to handle problems:

Sometimes a big event happens that changes everything. When it does, it tends to affirm the human tendency to treat big events as fundamentally different from smaller ones. That’s a problem, inside companies. When we put setbacks into two buckets —the “business as usual” bucket and the “holy cow” bucket— and use a different mindset for each, we are signing up for trouble. We become so caught up in our big problems that we ignore the little ones, failing to realize that some of our small problems will have long-term consequences —and are, therefore, big problems in the making. What’s needed, in my view, is to approach big and small problems with the same set of values and emotions, because they are, in fact, self-similar. In other words, it is important that we don’t freak out or start blaming people when some threshold —the “holy cow” bucket I referred to earlier— is reached. We need to be humble enough to recognize that unforeseen things can and do happen that are nobody’s fault.

There’s so much more to quote, but go read the book instead ;)

Little technical side-note: I did not type those quotes, but used Scanbot’s surprisingly well functioning OCR feature.